Supply-side economics — the notion that tax cuts for the rich pay for themselves via increased growth — is a kind of punching bag for progressives, and rightly so. Our economic experiment in the 80s was at best a mild boon for growth, and at worst, a profoundly anti-poor restructuring of America’s distributive institutions. That’s why conservatives can’t use the terms “supply-side”, “trickle-down”, or “Reaganomics” without getting ridiculed.

And so it’s no surprise that hard-left types, when debating housing policy, throw around “supply-side” as a derogatory way to describe market-based approaches. Superficially this is a fitting description: yes, we’re concerned with increasing the supply of housing, just as Reagan aimed to increase the supply of capital and labor. But the analogy falls apart in many ways, and it ends up lumping those who think zoning is the major roadblock to affordability in with the likes of Art Laffer. And that is unfair.

Macro vs micro

The first problem with comparing market-driven housing policy to supply-side economics is that they operate on two different levels of the economy. Supply-side economics is a macroeconomic doctrine; it aims to explain the behavior of the aggregate economy by studying the relationships between variables like tax rates, investment, and GDP growth. By definition it’s concerned with all markets at once. On the other hand, the market for housing is just that: a market. One market.

This distinction is important because our ability to understand individual markets is considerably greater than our ability to know anything, really, about how the economy as a whole works. Economists take a lot of heat in public discourse, but this criticism is directed towards the sexy topics — crises, recessions, government spending — almost all of which is macro’s turf. This stuff, supply-side theory included, is contentious because competing hypotheses are generally difficult to falsify. It’s nearly impossible to attribute to causality to any one policy in a $17 trillion, 300 million-person economy. But micro is less ambitious. Its foundations — scarcity, competition, supply and demand — are much more widely accepted than any macro theory, and by studying one market at a time, the questions it tries to answer are imminently more solvable. (Here’s Noah Smith making this exact point.)

So the problem with this comparison is one of scale: market-driven housing policy advocates are far more humble than supply-siders. We’re drawing on well-established principles to tackle a manageable question, whereas supply-siders are proposing some kind of Grand Unified Theory to explain everything at once. Who is more likely to succeed?

Mechanism of action

Supply-side economics, at least as a political ideology, is chiefly about cutting taxes on top earners. It works by changing the rules of the game so that rich people get more money. At time t, rich people people get x dollars in net income. At time t + 1, they get y dollars of net income, where y > x . Whether this creates secondary effects that benefit everyone else — indeed, this is its selling point — doesn’t matter. The mechanism is to give to the rich and pray that it works out okay. Supply-side economics may be pro-poor, but it is always and everywhere, by definition, pro-rich in absolute terms.

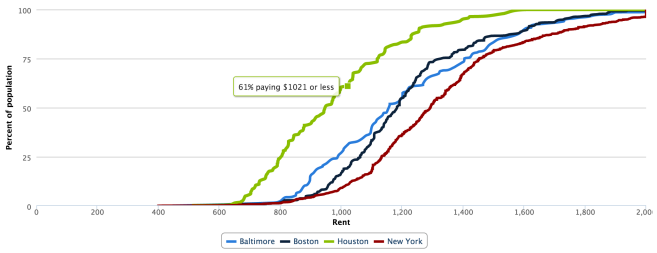

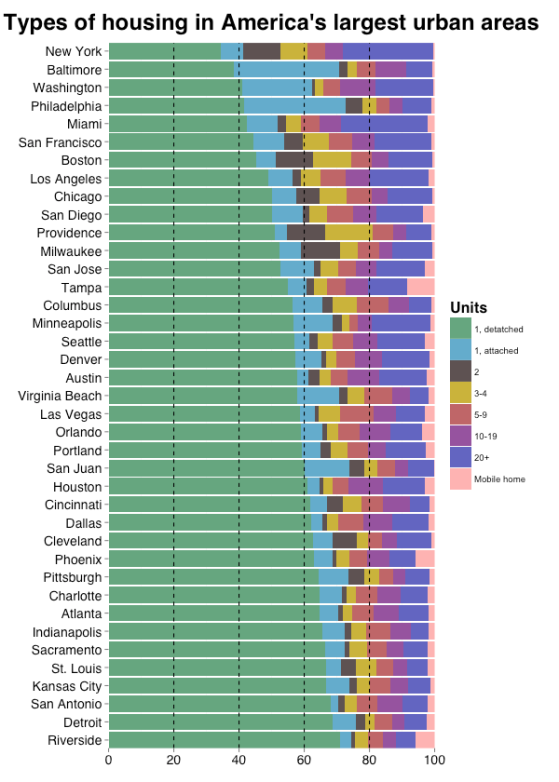

This is not the case with “supply-side” urbanism. Its mechanism of action is liberalizing land-use restrictions. (Yes, deregulation was a part of Reaganomics, but most people don’t think about telecom market structure as a core tenant.) Now, critics point to deregulation as being essentially pro-rich. It’s easy to see why people think this — we look around and see that private developers are only building fancy condos. If we were to upzone a block in Columbia Heights, the ubiquitously boxy units of DC luxury vernacular would no doubt eat it alive. But this is a problem at the margin rather than an inherent feature in the way that supply-side economics is unambiguously pro-rich. It’s a subtle difference. Whether private construction will cater to the non-rich is a function of how much housing we allow, as Let’s Go LA explains so well:

As an analogy, imagine if we only allowed 7,500 cars to be built every year. Auto manufacturers would only be making Maybachs and Maseratis, and they’d all be getting bought by the likes of people who own Mittal Steel and the Burj Khalifa. Now imagine if we built 750,000 cars a year. They’d still be unaffordable to most people but your techbros and finance quants would be able to buy them. Now imagine if we built 75 million cars a year. The global elite wouldn’t buy them all because it would be a terrible investment. New cars would be affordable to a wide range of people, and we’d have a healthy market in used cars – kind of like we do in the real world.

There’s nothing in the fabric of the universe that says zoning deregulation has to be regressive. It’s just a matter of getting the details right, which in most cases means taking it far enough.

Flexibility

Finally, the comparison breaks down in a third and perhaps most important way: “supply-side” urbanism is flexible; supply-side economics is not. Now, some utopian libertarian-types seriously think that mass upzoning is the be-all, end-all fix to urban housing problems. I am not one such person. But fortunately, it doesn’t have to be a universal solution; it’s just as useful as a starting point. We can pair market-based housing policy with virtually whatever else we want!

This is because upzoning is literally free. It requires no public money. That means budgetary resources stay/become available for whatever programs we think are worth funding. On the other hand, supply-side economics leaves a massive hole in the budget unless a) resulting growth is high enough that total revenue doesn’t fall or b) we cut spending. (Most economists think a) is BS.)

This unfortunate arithmetic means that trickle-down economics is inflexible. Let’s say that we do allow developers to build more housing, and yet some people still can’t afford rent. No worries — we can always give them cash, or create a refundable housing credit, or do whatever we need to do fiscally to help low-income residents afford rent. Supply-side is fundamentally different because its tax cuts eat up public money; by definition a supply-side agenda sets aside our budgetary resources for the rich.

~~~~

So, to summarize, “supply-side” urbanism is a misnomer. When leftists liken market-based housing advocates to supply-siders, they’re making a cheap and deeply flawed comparison. Unlike real supply-side economics, a market-based approach to urban housing affordability is a wholly compatible if not entirely necessary part of the progressive agenda.